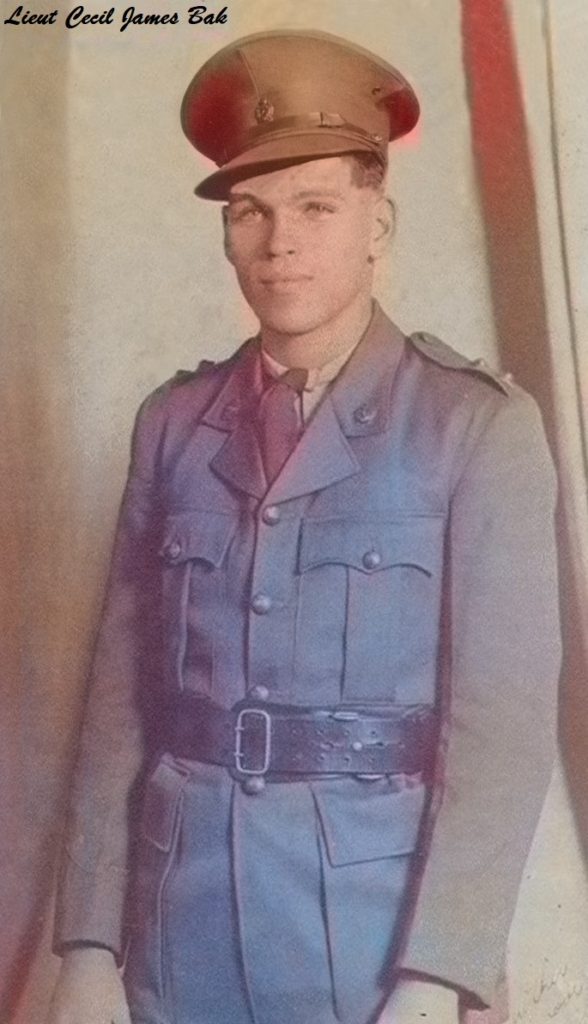

Lieutenant Cecil James BAK

31st/51st Battalion

By James Martin

Cecil James Bak QX 61455 (Q38802) was born in Brisbane on 8 April 1920, the eldest son of James and Alice Bak.

Cecil first went to Woree State School in 1926. The school was on the western side of the highway into Cairns, about 3.4 kilometres from the family home at White Rock, on the eastern side of the highway. After finishing primary school, Cecil attended Cairns High School.

His first job was as a clerk with Burns Philp & Co Limited, shipping and general merchants. This business serviced not only Cairns, but also all of Queensland.

There is no record of when Cecil joined the Citizens Military Forces 51st Battalion. However, he completed and qualified as corporal with that unit on 14 September 1939.

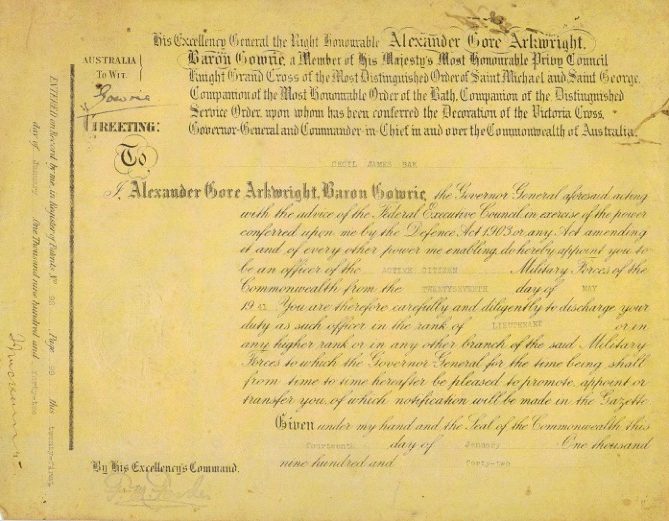

In July 1940, as a sergeant, he completed an individual training course from 4-15 March at the Northern Command Training School, Enoggera. He was commissioned on 27 May 1941. From 7-30 July 1941, he undertook a weapons training course and on 15 July 1944, he joined the AIF.

On 24 January 1942, Cecil was married to Dorothy May (née Johnson) in the Methodist Church, Cairns. Dorothy was the fourth of five daughters of Henry William (Willo) and Caroline Johnson.

On 11 February 1945, Cecil, a lieutenant with the 31st/51st Battalion, was killed at Tsimba Ridge, Bougainville. His Army record states that death was by sniper fire and another account states artillery fire.

Lieutenant Cecil James Bak is buried at Bomana War Cemetery, Port Moresby.

In Cairns on 29 June 1945, Dorothy (now widowed) gave birth to Carol June.

Carol grew up in a caring community with friends of her mother’s who were able to tell her about the father whom she never knew. Carol tells with pride, some of those stories:

“During and after the war, Cairns was a small place where everyone knew everyone else. Romances were the talk of the town; entertainments and outings were a walk in the park or an evening at the cinema or dance hall. Cecil was a handsome dance partner and Dorothy realised she had some competition, so she decided to become more adept. Dancing and singing proved to be pleasurable pastimes well into her eighties. Dorothy died in Cairns on 10 June 2011.

Carol left school at the age of 14 and started work at Harris Brothers, who had moved their drapery and mercery business from Sydney. One of the brothers had served in the First World War.

Carol discovered that customers frequently asked kindly about her mother and said that they remembered Cecil and what a lovely person he and all his family were. It was a consolation for the young teenager to hear that her father was so well regarded.

One of the ladies was a dressmaker who offered to help Carol learn the finer points. She was the wife of Sergeant Tom James who was in the same unit as Cecil. When the fighting on Tsimba Ridge was over, Cecil told the chaps to go and have a cup of tea and a biscuit with the rest of the unit. When they hesitated, Cecil ordered them to go. Sergeant Tom James recalled sadly: “The rest is history”.

Tom’s wife said, “he carried that order from Cecil all his life”. Years later, when Tom came to collect Carol to attend a function of the 31st/51st Battalion, Tom said to Carol: “The wrong man died. It should have been me”.

Another man under Cecil’s command asked Cecil if he could give him a haircut – and Cecil did. When the man returned home to Cairns, he told everyone: “the last thing Lieutenant Bak did for me was to give me a haircut”.

Carol has frequently mused: “I can only wonder how different my life would have been had my father been able to come home”.

Cecil’s brother, Les, also served in the Second World War. He was very upset when he heard of Cecil’s death. Years later, he told his niece Carol, that when he heard (the day after) that Cecil had been killed in action, he sat in the jungle clearing, wishing that he could draw the enemy’s attention and that he too, would die. Les was awarded the Military Medal.

On 30 April 1966, Carol married Gary Thomas West. Carol recalls years later learning from her husband Gary that his father, Thomas Henry West, a medic during the battle, carried Cecil from the battlefield to a waiting barge where he later died.

Cecil’s story follows.

| FINAL ATTACK ON TSIMBA RIDGE WHERE CECIL WAS KILLED (FROM THE BOOK BY MAJOR W.E. HUGHES) |

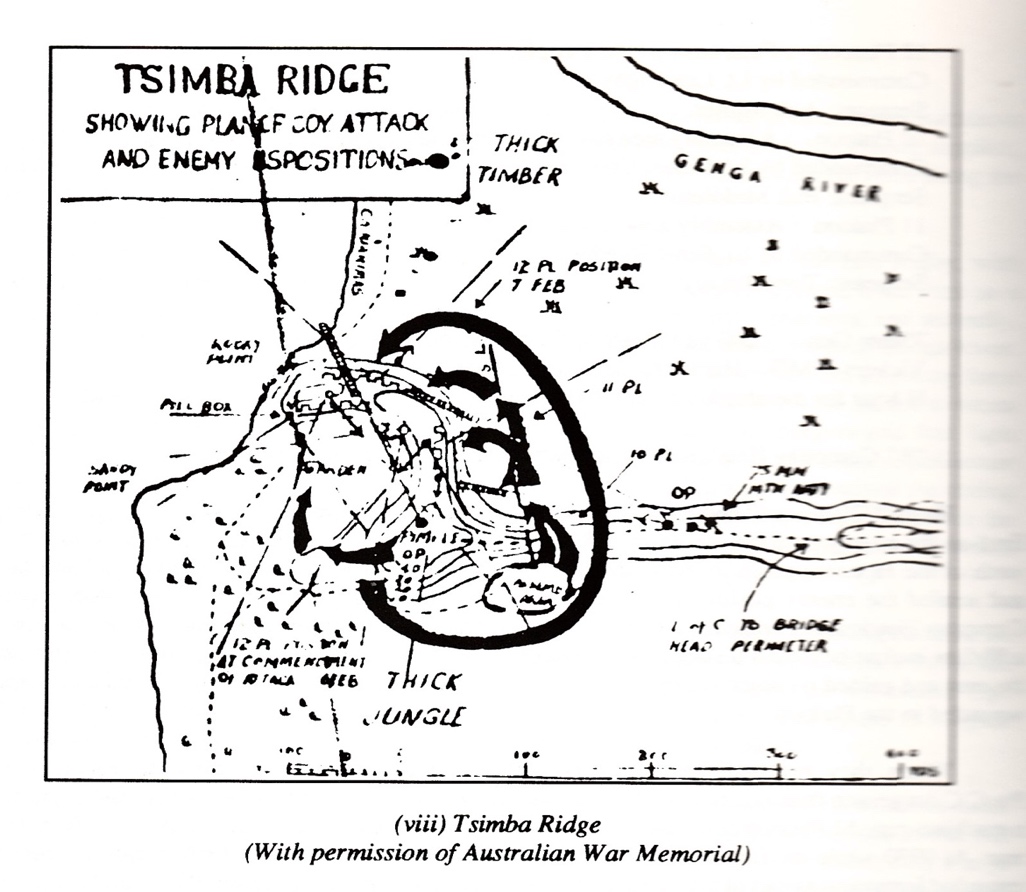

B Company was pulled out of the line for a day’s rest on 5 February. On 6 February, 1945, commanded by Capt Nick Harris, B Company was given the task of clearing the Japanese from Tsimba Ridge. Dispositions for the attack were as follows:

12 Platoon: Firm base on the Pimple

10 Platoon: Assembly area east of the Pimple

11 Platoon: Assembly area east of the Pimple

75mm Gun: 200 yards east of the enemy positions

Vickers MMG: Harassing fire until H hour

H hour for the attack was at 0900 hours

B Company Headquarters accompanied 11 Platoon in the attack.

“From 0830 hrs until about 0900 hrs on 6 February, over 500 shells and mortar bombs were fired on the enemy positions on Tsimba Ridge. A mountain gun was brought forward within 200 yards of the Japanese position. After the shelling, Corsairs and Wirraways moved in and bombed and strafed the enemy positions.

“Under cover of the supporting fire, 10 and 11 Platoons plus Company Headquarters reached the start line south-east of the amphitheatre. They advanced down a 50 foot incline beyond a distance of 200 yards. 10 Platoon attacked the centre of the ridge from the east and gained its objective by 0925 after killing five Japanese. Three were killed and seven wounded in the Platoon.

“When they reached their objective, 10 Platoon came under heavy automatic fire. Pte C.C. Jorgensen courageously rushed the Japanese weapon pit, killed the occupants and captured a machine gun. 11 Platoon continued to move north to circle the western part of the ridge from the rear. At 0930, while the firm base at the Pimple held, 12 Platoon advanced into a garden area in extended formation as part of a deceptive plan. The Japanese garden was covered in waist high grass and pawpaw trees. They advanced about 75 yards up the ridge escarpment, when a woodpecker (machine gun) opened up from a dugout position about six feet above the garden level. This gun had not been observed at any time previously and fired through a slit six inches wide and four feet long. The platoon went to ground and was pinned there having lost four men and it withdrew after dark.

During this advance, Cpl G.C. Miller took command of two sections which had lost contact with their platoon and he led them forward to their objective under fire which wounded six men. The enemy directed heavy fire on the platoon to prevent this threat, enabling 10 Platoon, without suffering heavy casualties, to reach and capture its objective. 11 Platoon moved to the right and came under fire from a heavy machine gun, but succeeded in capturing the northern brow of the ridge. By 1130 hours, 11 Platoon reached the high ground on the western end of the north side of the ridge but could not advance to the enemy positions on the south side.

“The Japanese were then surrounded but the attack had cost the Australians nine killed and 20 wounded. These losses were not surprising. The enemy had a continuous communication trench along the crest and on both sides of the ridge. Forward of their trenches were weapon pits with log roofs commanding a clear field of fire across an area offering little cover except at the inner edge of the beach where a line of lofty casuarinas grew.

“So far five enemy dead had been counted, one heavy machine gun and a Nambu (pistol) had been captured. From about 1100 hours until about 1230 hours, our positions were accurately shelled by the enemy and direct hits were made on the Pimple, resulting in three men being killed and five wounded. Next morning the enemy counter-attacked and was repulsed. He clung doggedly to his remaining pocket on the tip of the western edge of the ridge.

“On the early morning of 9 February, three aircraft bombed the enemy positions. Six bombs were dropped with only two exploding, but after a mortar bombardment, B Company advanced and occupied the remainder of the ridge without opposition. Six Japanese were found dead.

“Just on midnight, the enemy launched their last attack but were beaten off with at least two Japanese killed. The night attack was helped by poor visibility and after withdrawing, they fired random shots and mortars, banged tins and equipment together and made a great din. Everyone waited for the Banzai charge that never came. After this noise, an earth tremor shook the area.

“Suddenly the troops became aware that the ridge was strangely silent, but it was not until morning that it was discovered that the enemy had withdrawn by barge during the night. They had landed on the narrow beach north of the ridge. The din created during the night was probably caused to conceal the sound of the barge.

“During the battle, personnel of 16 Field Company commanded by Arthur Graham, brought TNT satchel charges to Tsimba Ridge to destroy the pill boxes. Because of heavy enemy fire they were unable to get near them and were forced to abandon the idea. The sappers then helped to carry out the dead and wounded. Lt Col Kelly later expressed his appreciation for their assistance.

“It was estimated that in the three-day battle, 66 Japanese were killed by members of B Company in the Tsimba area. Spoils of war captured were four field guns, 10 machine guns, three anti-tank guns, 86 rifles and a large quantity of ammunition.

“By 10 February the area south of the Genga River was cleared of the enemy by D Company and patrols cleared the north bank of the river.

“On 11 February the Japanese were forced out of their position astride the track some 150 yards beyond the river. The Japanese artillery then frequently harassed the advancing battalion. On that day Lt Cecil Bak (Cairns) and his batman Pte Joe “Hawk” Lewis (Home Hill) were killed by artillery fire while having a cup of tea on the beach at the rear of Tsimba Ridge. Correspondents and observers described the battle as the bloodiest fought on Bougainville up to that time.

“C Company acted as stretcher bearers during the final attack on Tsimba Ridge and were kept busy. A volunteer bearer was Father Tom Ormonds, a Catholic Chaplain, who carried stretchers every day. He was a man older than the troops he served but it never worried him. He was an example to them all, particularly as the stretcher parties were at times ambushed.

“The battalion Quartermaster, Captain Ben Kahler, visited the Ridge the morning after the final attack and spoke with Lt Lionel Coulton, Commander of 10 Platoon, who said “Have a cup of tea with my platoon”. All that remained were three men and the officer.

TSIMBA RIDGE VICTORY – AN HEROIC WAR CHAPTER

The following article is an extract from a wartime issue of the Herald Newspaper. The story was written by Victor Wouldcroft, Herald War Correspondent.

BOUGAINVILLE (Delayed) – Tsimba ridge fell to Australian troops after 20 days of bitter fighting. It formed the most heroic chapter in the story of the Australian action in Bougainville. It was after the hardest fighting that our troops took by assault a formidable defence system manned by a fanatical enemy. As many of the eye witnesses to the individual acts of heroism lie in the shadow of Tsimba Ridge, or are wounded in hospital, it will be some time before this proud Queensland unit, which included many from other Australian states, can give a clear picture of what happened in the heat of attack and counter-attack.

“The loss of Tsimba Ridge was a major defeat for the Japanese rearguard action being fought along the north coast, while enemy reinforcements were ferried from areas near Buka passage. Today, Tsimba Ridge is littered with the wastage of war, twisted and rotting jungle, shrapnel-scarred trees and the darkness of the battlefield. It is too early to assess the cost in lives.

“Tsimba Ridge and the Genga River are linked in the two front battle. After the Australians obtained a foot-hold on the Pimple, a feature 75 yards from the ridge, ten days before its fall, a strong force of Australians were ferried silently in twos across the Genga River in a rubber boat to establish a perimeter between Tsimba and the enemy forces.

“This victory defeated banzai charges, night assaults and vicious daylight onslaughts in an effort to repel our troops back across the river. Though bound by their perimeter, they harassed the enemy in deep and bold patrols each day. The first 17 days of the attack on Tsimba Ridge, were a series of courageous efforts by patrols and sections to take the steep slopes of the 60 foot ridge to the enemy gun positions. These were dug into rocks 10 feet deep and covered by three feet of stone, with an interlacing trench system commanding all approaches. This allowed them to bring terrific fire to bear.

“On the 18th day, the Australians launched a three-pronged attack, the first from the north-east, another from the east and the third across a banana and pineapple plantation. A third of the ridge fell sheer into the sea and the other end abutted the narrow neck into the plantation. The attack through the plantation met with heavy fire from machine guns and rifles and although there were heavy casualties, the remainder made a supreme effort to secure the ridge, but they were forced to withdraw.

“The Pimple was kept under very heavy fire to prevent any reinforcements from reaching the platoon. In the meantime other attacks were pressed even closer and there were times when the enemy hurled grenades as the Australians climbed up the ridge. They drove the Japanese off the crest into dugouts and defences down the other slope and into a small area at the north end of the ridge. During the night the Japanese staged a suicidal counter-attack which was beaten off. They withdrew to main defences 30 yards from our weapon pits where they were heard jabbering excitedly.

“Enemy artillery then fired on our support troops on the Pimple. The fire failed to dislodge our infantry, crouched in muddy bottomed holes. Some of these had been dug by our troops under fire because the Japanese pill-boxes were uninhabitable.

“On the 19th day no conclusive action was possible as the enemy were constantly shelling our positions. Counter fire was directed on the ridge by mountain guns and mortars, while sniping and repeated heavy woodpecker and Vickers gun fire kept the troops’ heads down.

“On the 20th day – the day of victory – Corsairs and Wirraways, piloted by New Zealanders and Australians, bombed Japanese positions with 250 pound delayed-action bombs. After the last bomb had burst the Australians attacked. The enemy had fled. It was not known whether they escaped in the darkness, having had enough of the fight, or decamped in the jungle after the bombing. Bodies found were ostensibly victims of the bombing that showed that at least a few had remained to the last.

“Meanwhile, the battle in the bend of the Genga continued. Troops, though weary and wracked by strain of unending conflict, beat back attack after attack. In one of these, a Japanese officer rushed a position with a drawn sword. He died! Many of the Australians were at school five or six years ago. They had fought like tigers. They sent out bold patrols to disorganise enemy plans and little battles took place daily behind the enemy lines.

“When Tsimba Ridge fell, the beleaguered Genga force of weary troops pushed the Japanese back from their positions only 30 yards outside the perimeter. The battle is continuing along the coast road 200 yards further north, where the Japanese are making another stand. Behind them lies an area of defences which might bring about another large-scale action in the near future.

“Today, on the crest, men who had not changed clothes for a fortnight ripped off their muddy garments, dried them in the sun, shook out the dust, and donned them again. Bewhiskered faces, lined with the strain of combat, justifiably displayed the silent pride they felt for their achievement. It was tempered by grief at the loss of comrades.

“Nearby, two infantrymen made a crude cross for a soldier who died in an attempt to wipe out a heavy machine gun post, which had caused casualties to his section. Personal belongings lay everywhere – swords, picture postcards and mail. A stinking heap of rotting rice and taro was being gorged by sea crabs. Heavy woodpeckers poke their snouts from narrow slits. Pistols, mortars, bayonets and other equipment were included in the booty. One machine gun was sent to the rear with a label and the request that it be sent to a branch of the Returned Soldiers’ League in Queensland.

“Tsimba Ridge, as it stands, scarred by bombs and shells, above the little Australian cemetery, is a monument to one of the most courageous actions fought by Australian troops.”

“Les Payne of 11 Platoon, now living in Bowen recalls:

“Captain Nick Harris in a talk with me about the attack said that we should take the ridge in about 10 minutes. The two platoons were at the start line at 9am and started up the slope, with 200 yards under fire. 11 Platoon could not get as far towards the coast side as had been expected, so as 10 Platoon went up the centre, 11 Platoon advanced up the right flank and in some of their area.

“It was at this time that I felt proud to be a member of 31/51st Battalion and an Australian. Our men were going down and could say blood flowed down the ridge but not a man faltered. In addition to the intensive fire that poured down on us by the Japs, we shared some of our own artillery fire with them. Well, the ten minutes turned into four long days, and we had only gone in with our weapons and no food or water.

“I had the job on the fourth day, being a scout to check the Jap trenches after an air bombing, to find if they were still there. I was happy to state all I could find were dead Japs, so Tsimba Ridge was ours, but it had cost our company nine men killed and over 20 wounded. And that was from a company very much under strength, because of former battles. Japanese losses were established at 66 killed. The company captured four field guns, three anti-tank guns, nine machine guns and 86 rifles.

“Tsimba Ridge was no mopping up operation, but has been quoted as one of the toughest actions fought in the South-West Pacific region. If it was not, I would not like to be in one that was tougher.”

| COMMEMORATIVE INFORMATION

PORT MORESBY (BOMANA) WAR CEMETERY – A4. C.7. |

The War Cemetery lies approximately 19 kilometres north of Port Moresby on the road to Nine Mile, and is approached from the main road by a short side road called Pilgrims Way.

After the landings at Lae and Salamaua, Port Moresby was the chief Japanese objective. They decided to attack by sea and assembled an amphibious expedition for the purpose which set out early in May 1942. They were, however, intercepted and heavily defeated by American air and naval forces in the Coral Sea and what remained of the Japanese expedition returned to Rabaul. After this defeat they decided to advance on Port Moresby overland and the attack was launched from Buna and Gona in September 1942.

On Bougainville, the largest and most northerly of the Solomon Islands, the enemy, early in 1942, established a considerable force almost without resistance and developed a useful base. This they held until Americans and Australians commenced offensive operations towards the end of 1943, when Bougainville was the only one of these islands remaining in Japanese hands. By August 1945 when the Japanese surrendered, most of the island had been recovered.

Those who died in the fighting in Papua and Bougainville are buried in Port Moresby (Bomana) War Cemetery, whither they were brought by the Australian Army Graves Service from burial grounds in the areas where the fighting had taken place. The unidentified soldiers of the United Kingdom forces were all from the Royal Artillery and captured by the Japanese at the fall of Singapore. They died in captivity and were buried on the island of Bailale in the Solomons. These men were later re-buried in a temporary war cemetery at Torokina on Bougainville Island before being transferred to their permanent resting place at Port Moresby.

On a hill above and behind the cemetery, to the right of the centre, stands a rotunda of cylindrical pillars which is the memorial to those men of the Australian Army (including Papua and New Guinea local forces), the Australian Merchant Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force who lost their lives in the operations in Papua and who have no known graves. Men of the Royal Australian Navy who lost their lives in the south-west Pacific region and have no known grave, but the sea, are commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial in England along with many of their comrades of the Royal Navy.

Cecil and Dorothy on their wedding day. Cecil was married to Dorothy May Johnson in the Methodist Church, Cairns on 24 January 1942.

Cecil’s grave at Bomana War Cemetery, just north of Port Moresby.