Private Henry Martin

52nd Battalion AIF

By Warren Martin

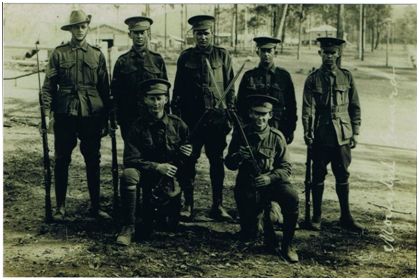

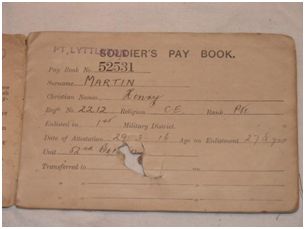

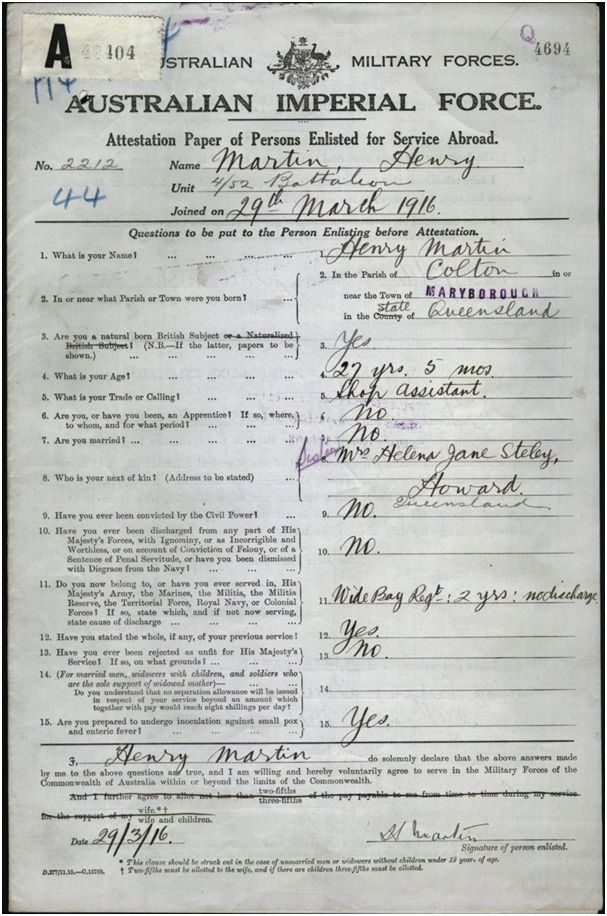

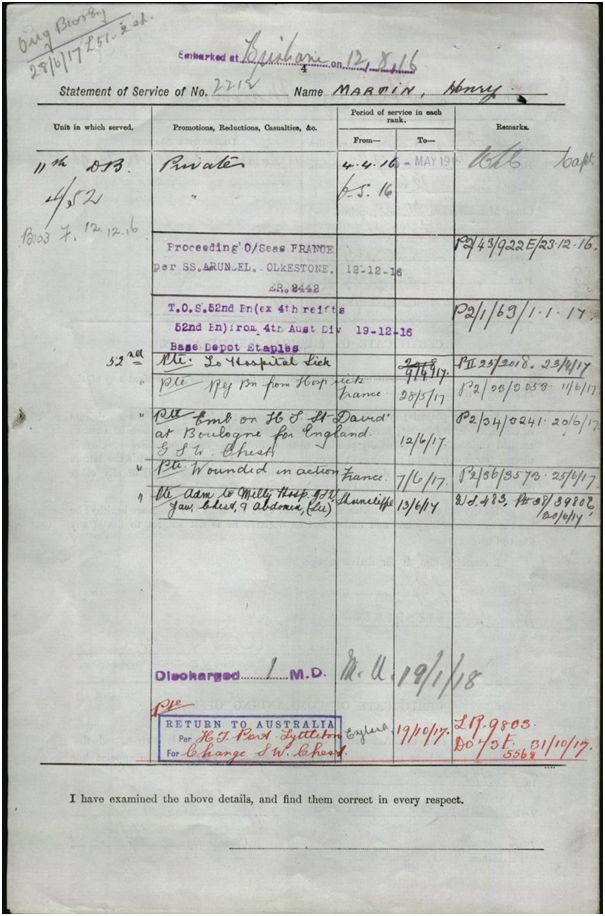

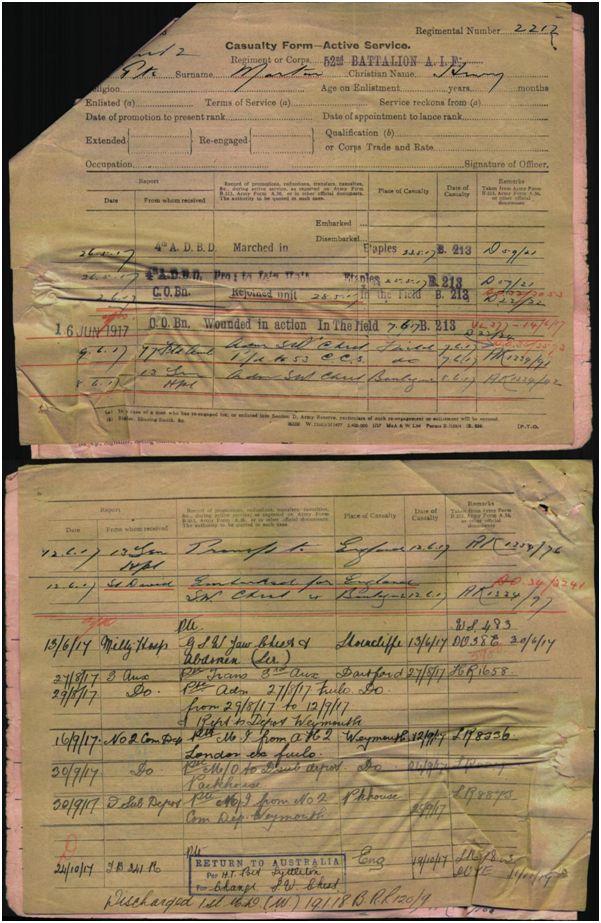

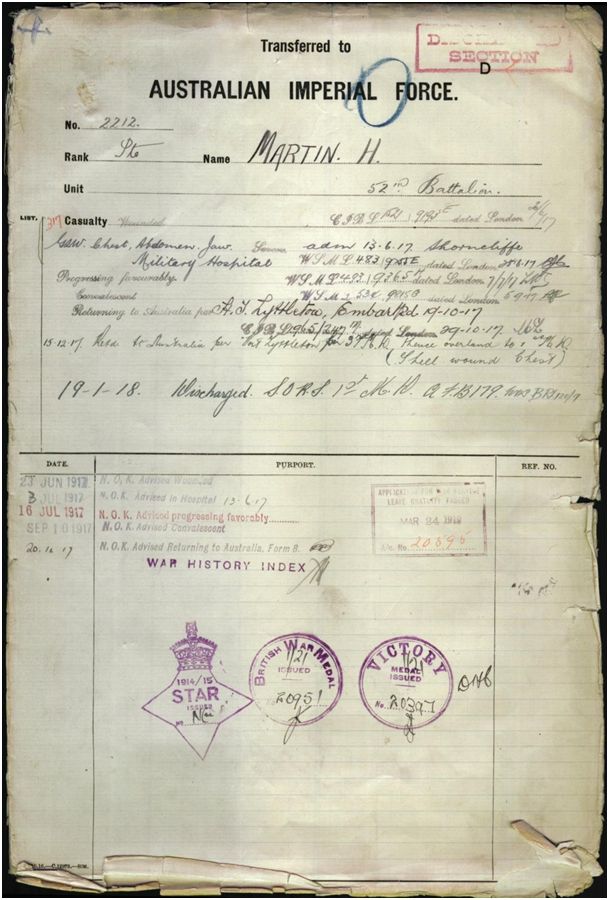

Private Henry Martin Regimental number 2212 Place of birth Maryborough Queensland Religion Church of England Occupation Shop assistant Address Howard, Queensland Marital status Single Age at embarkation 27 Next of Kin Sister, Mrs Helena Jane Steley, Howard, Queensland Enlistment Date 29 March 1916 Unit name 52nd Battalion, 4th Regiment AWM Embarkation Roll number 23/69/3 Embarkation details Brisbane, Queensland, on board HMAT A42 Boorara on 16 August 1916 Rank from Nominal Roll Private Unit from Nominal Roll 52nd Battalion Fate Returned to Australia 19 Octover 1917 Henry Martin was a 27 year old Shop assistant from Howard near Maryborough. He enlisted in the AIF on the 29 th March 1916. He was initially enlisted in the 52 nd Battalion and after some training embarked Brisbane, Queensland, on board HMAT A42 Boorara on 16 August 1916 bound for the battlefields of the Western Front.

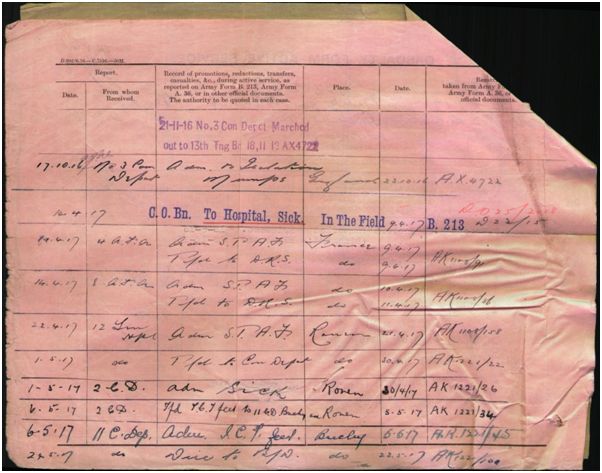

He would arrive in England in late 1916 having missed the first major actions by Australians after Gallipoli at Fromelles and Pozieres where thousands of Diggers lost their lives. After a bout of mumps, Henry would arrive at Etaples in France on the 19 th December 1916 training and labouring behind the lines during the harsh winter in Belgium.

The 52nd Battalion was raised at Tel el Kebir in Egypt on 1 March 1916 as part of the “doubling” of the AIF. Approximately half of its recruits were veterans from the 12th Battalion, and the other half, fresh reinforcements from Australia. Reflecting the composition of the 12th, the 52nd was originally a mix of men from South and groups mainly comprised men from Queensland. The 52nd became part of the 13th Brigade of the 4th Australian Division.

After arriving in France on 11 June 1916, the 52nd fought in its first major battle at Mouquet Farm on 3 September. It had been present during an earlier attack mounted by the 13th Brigade between 13 and 15 August, but had been allocated a support role and missed the fighting. In this second attack the 52nd had a key assaulting role and suffered heavy casualties – 50 per cent of its fighting strength. The battalion saw out the rest of the year alternating between front line duty, and training and labouring behind the line. This routine continued through the bleak winter of 1916-17.

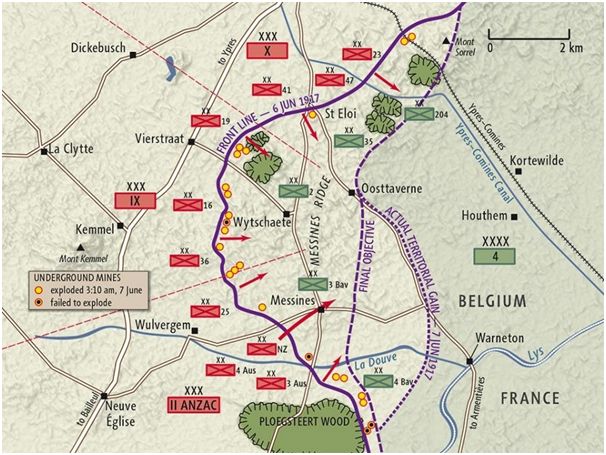

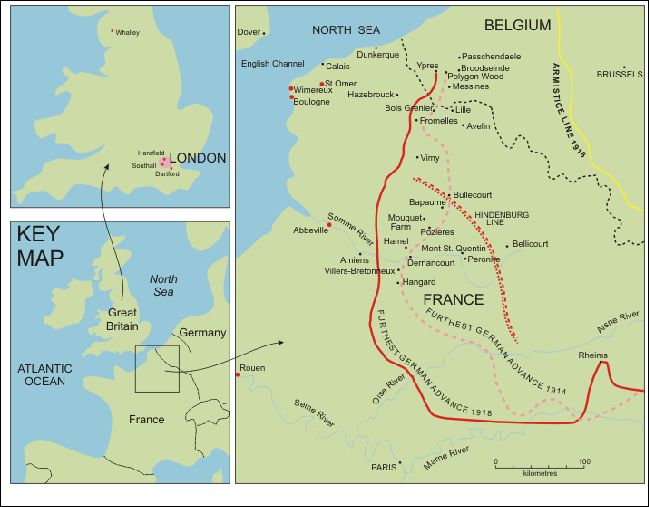

Early in 1917, the battalion participated in the advance that followed the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line, and attacked at Noreuil on 2 April. Later that year, the focus of AIF operations moved to the Ypres sector in Belgium. There the battalion was involved in the battle of Messines between 7 and 12 June and the battle of Polygon Wood on 26 September. Another winter of trench routine followed.

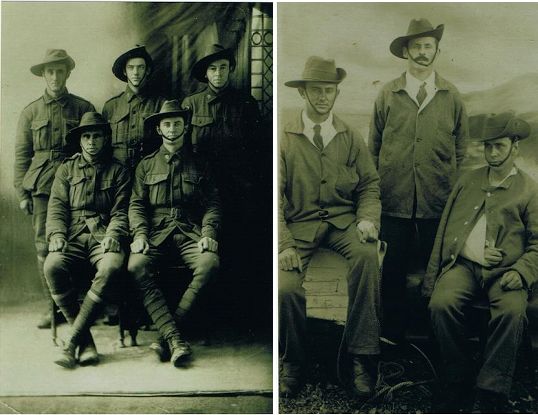

Henry and the 52nd Battalion moved to Vignacourt in mid December. They were to remain here until early January, billeted and training for further deployment. It is extremely possible that Henry had his photo taken by the Thuilliers while there. He may even have visited Naours caves and left his name there. The Battalion spent time at Villers-Bocage, Fricourt and finally Flers.

As February came the Battalion was involved in and out of the lines around Flers. It snowed heavily and conditions would have been terrible for soldiers both in and out of the lines. Shelling continued during the entire time. In April at Buire and Lagnicourt the Battalion was in the front line and assisted in the capture of Noreuil. On the 29 th April time was even granted for polling for the Federal election of 1917.

As the weather improved the Battalion was rested and moved back to Belgium via Abbeville, Boulogne, Calais and Hazebrouk. Billeted near Caestre in late May they were visited by General Plummer. By late May they finally were in the Ypres sector in Belgium.

It was here that the Messines Ridge was a major objective. The Battalion was in and out of the front doing reconnaissance waiting for orders to be given.

It was during events at Messines Ridge that Henry was to be severely wounded. This was to eventually lead to his return to Australia. The war for Henry on the Western Front was over.

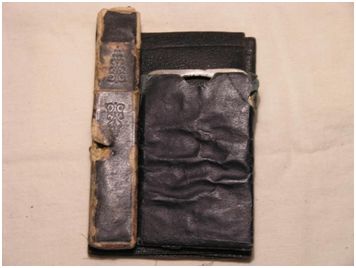

“A bullet hit the left side pocket of his tunic, shattering his razor and passing through his paybook and hit his steel mirror. The bullet hit the mirror and missed his heart. The bullet stayed in his body after he was repatriated to England. The bullet remained there for over 10 years until it moved closer to his spine and was eventually removed at Maryborough Hospital in 1927. “

Being the only male in the family this event saved the Martin family !

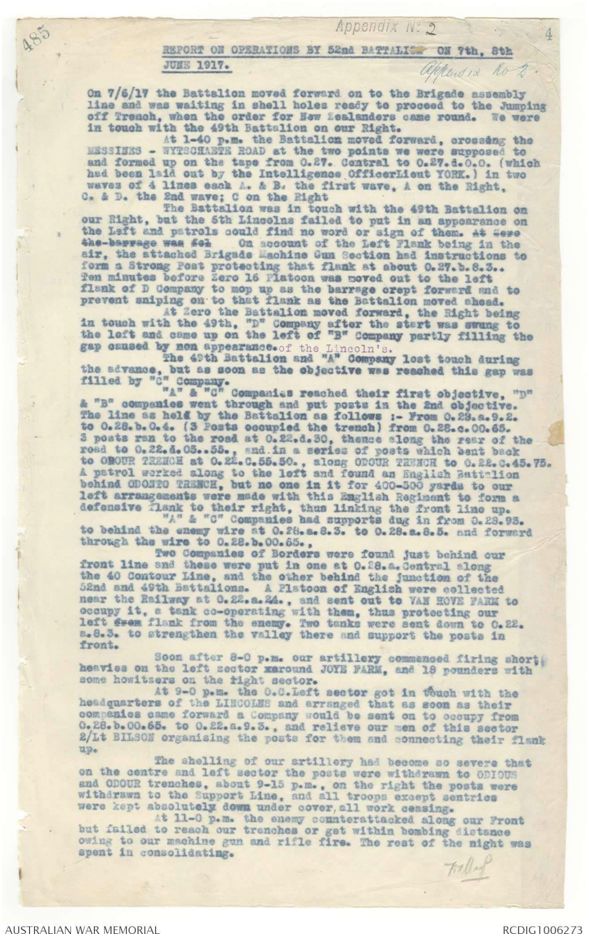

The 52nd Battalion War Diary below gives the events of early June.

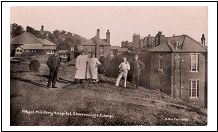

Henry was treated at a local field hospital in the field before being repatriated to Boulogne for further treatment. He was transferred to the Military hospital at Folkstone and eventually transferred to the 4rd Auxilliary Hospital at Dartford in England. Finally he was to depart for Australia on the 19th October 1917. He was discharged unfit from his active service in January 1918.

NOTE BY WARREN MARTIN, GRANDSON OF HENRY MARTIN:

With reference to the quote on Page 5 of this document:

Something which has puzzled me for a number of years is how the stainless steel mirror in Grandad’s breast pocket could have deflected the shrapnel ball, thus saving his life.

After Grandad passed away my dad had the contents of Grandad’s breast pocket and when Dad passed away they were passed on to me until Uncle Col requested that all items be collected and placed in the Maryborough Military Museum for safe-keeping. We have been told that the mirror deflected the shrapnel ball thereby saving Grandad’s life and I also remember being told that it passed through his liver. But the mirror is the only item that was not damaged. By lining up the various items I believe Grandad had his paybook at the back, his wallet in front of his paybook and his razor and mirror side by side at the front of his pocket. The stainless steel mirror was inside a leather cover. Neither the leather cover nor the mirror suffered any damage. Because his razor was in its case most of the shattered parts were contained and can be pieced together. From the trajectory of the shrapnel ball through these items I feel it is unlikely that it ended up near his spine as it struck him in the left side of his chest and was travelling further to the left.

After studying extracts of Grandad’s medical records, provided by the Australian War Memorial, I was surprised to see that he actually received three separate wounds from the one incident on 7 June 1917. His medical records indicate that he received wounds to the jaw, chest and abdomen. After my visit to the Western Front Battlefields and the numerous military museums in the towns in those areas I now understand how the shrapnel rounds were calibrated and adjusted so as to explode overhead to cause maximum damage. I feel confident that it was three shrapnel balls that struck Grandad and the one that was removed through his back 10 years later was the one that caused his abdominal wound, passing through his liver and coming to rest near his spine. The injury to the jaw must have been relatively minor as no family members have ever mentioned that injury and nobody is aware of any facial scarring. The shrapnel ball that struck Grandad in the chest must have been removed while in the military hospital before his discharge.

A bit of extra information. Dad had said that Grandad walked with his full kit and rifle to the medical aid post, waited his turn to be treated, only to be told it was for New Zealand soldiers only. He was offered a lift to the Australian medical aid post but he refused the offer and walked. Having seen a map of the Messines Ridge battlefield, showing where the various divisions were lined up for the assault, Grandad was in the Fourth Division and immediately to their left was a New Zealand Division, hence the confusion at the medical aid post. We can now only speculate as to the reason for the story about the mirror deflecting the shrapnel ball. Knowing that Grandad did not like to talk about it, perhaps it was the simplest way to explain to his children how fortunate he was to have survived the ordeal.

ANZAC Biographies

On our website you will find the biographical details of ANZAC (as well as British) servicemen & women whose medals or other memorabilia form part of the collection on display at the Maryborough Military & Colonial Museum, Maryborough, Queensland, Australia.